Hummingbird, 1967

This work showcases Csuri’s exploration of natural themes. Movement is achieved through distortion, much like a child twisting and rotating a paper hummingbird. The child knows it cannot flap its wings, but let's pretend it can. Then the hummingbird gradually collapses into a single line, only to reappear and move in an opposite direction. The computer has a perfect memory and can make exact copies of everything. After several more explorations and variations, the watching intelligence decides "time is up" and slowly erases the hummingbird, returning to empty space.

“Hummingbird” is one of the earliest computer-animated films by Csuri. Aside from creating pioneering computer graphics systems, Csuri is recognized for introducing figuration into the language of computer graphics, which was often seen, even by artists, as a tool for visualizing abstract mathematical formulations. While “Hummingbird” creates a picture of its titular animal, the hummingbird’s ultimate, abstract annihilation also points to the compatibility between abstraction and figuration allowed by computer animation.

To make the film, over 30,000 individual images generated by a computer were drawn directly on film using a microfilm plotter. Each frame was programmed using one punch card, an example of the complex and labor-intensive operations required by early computer animation. The prelude to “Hummingbird” provides an overview of the way in which the film was made—a useful primer for much computer-generated art of the time.

In 1968, The MoMA organized a program of computer-generated films with programmer Ken Knowlton, who is well known for his work at Bell Labs with filmmakers including Stan VanDerBeek. Presented in conjunction with the exhibition The Machine as Seen at the End of the Mechanical Age, the film program included Csuri’s “Hummingbird” alongside films by John Whitney. Not long after its screening, “Hummingbird” was purchased by the Museum, becoming one of the first computer-generated works to enter MoMA’s collection.

In the Permanent Collection of the MoMA

“What Csuri did was ahead of his time. The film “Hummingbird”, 1967 anticipated the future.”

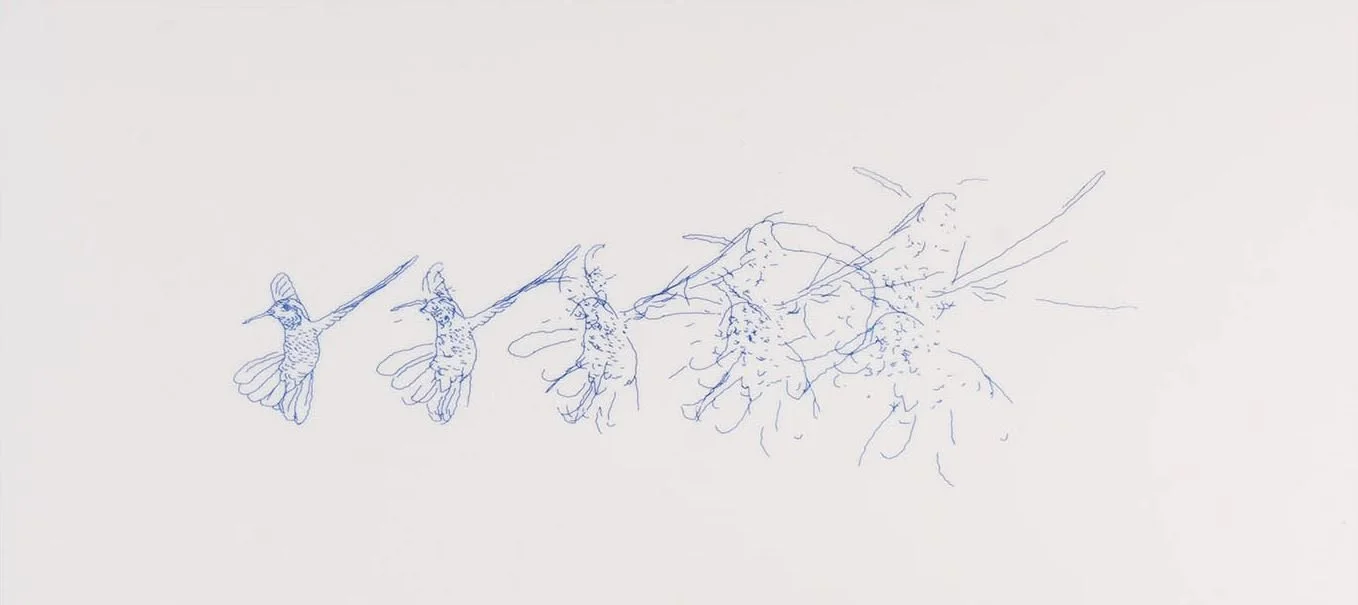

Hummingbird II, 1967

“Hummingbird II” reflects Csuri's early fascination with fragmentation, especially in its exploration of the relationship between form and abstraction. “Hummingbird II” is one of the few early works by Csuri that features a photo screen on Plexiglas as its final form.

Photo silkscreen on Plexiglas | IBM 1130 and drum plotter | 18” x 30” | Private Collection

“Hummingbird anticipates the future when computers will have the ability to think for themselves. The film begins with empty space and the idea the computer has an intelligence and is drawing a hummingbird. A drawing is being created with the science fiction notion of artificial intelligence and its implications for the future. An artist's hand is not making the line segments instead some unseen mysterious force is in charge. The force breaks the drawing into moving line segments which become increasingly chaotic or abstract and play with aspects of reality. Movement is achieved through distortion much like a child twisting and rotating a paper hummingbird. The child knows it cannot flap its wings but let's pretend it can. Then the hummingbird gradually collapses into a single line and reappears and moves in an opposite direction. The computer has a perfect memory and can make exact copies of everything. After several more variations the intelligence as it watches the clock, decides time is up and slowly erases the hummingbird to again become empty space.”

- Charles Csuri

Private Collection